Stalking the Wild Banana

Mr. Sachter-Smith, 35, caught the banana bug when he was 14, on a trip with his mother to Washington, D.C., where he saw banana plants in her friend’s yard. The friend said they weren’t trees, that she could dig them up for winter, stick them inside and replant them when it warmed. When he returned home to Colorado, he started growing them as house plants. “I was trying to figure out what is a banana plant,” he said. “It’s just been a never-ending quest since then.”

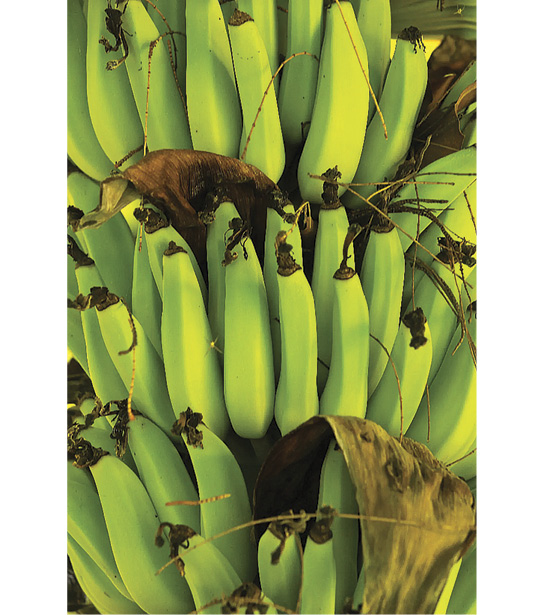

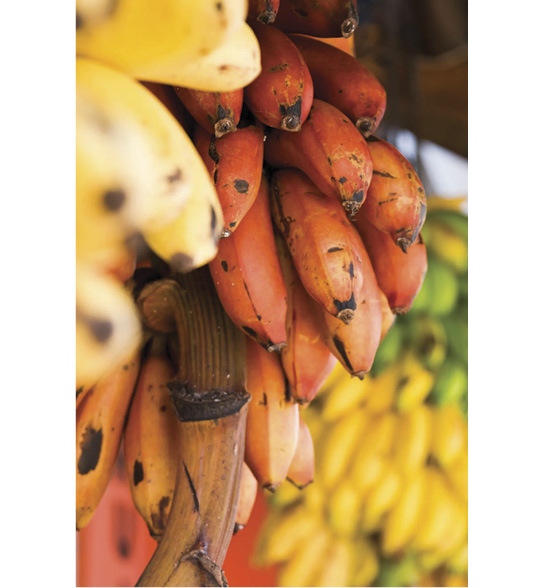

Mr. Sachter-Smith left banana-inhospitable Colorado to study tropical plant and soil science at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, ultimately earning a master’s degree. His global quest has introduced him to bananas that are egg-shaped and orange, a foot long and pale yellow, sausage-stubby and green. They are eaten fried, roasted, boiled and as is, but also grown for pig feed, decoration and weaving fabric. In Papua New Guinea, where Mr. Sachter-Smith has gone on two expeditions hunting for bananas, their names carry many meanings: “young men” (mero mero), “can feed a whole family” (navotavu), “something that was fought over” (bukatawawe), “breast” (nono).

You probably know just one banana: long, yellow, kind of flavorless. You eat it plain, put peanut butter on it, or toss it, overripe, in the freezer to make banana bread someday. (You won’t.) Its name, Cavendish, comes from a 19th-century English duke who was sent a package of the bananas and whose gardener grew them in a greenhouse. The Cavendish now accounts for almost half of all bananas produced globally and nearly all exports. It holds a Guinness World Record as the most eaten fruit.

But for years, scientists have warned that fungal diseases like black sigatoka and Tropical Race 4 could wipe out this monocrop, just as a fungus annihilated its predecessor, the Gros Michel, in the 1950s and 1960s. Genetic engineering and breeding are the most likely solutions, so scientists have built a stash of backup bananas from around the world, with genes that might someday see action on the global market.

About 170 of Mr. Sachter-Smith’s finds reside in the International Musa Germplasm Transit Center, a gene bank in Belgium that safeguards the in vitro DNA of more than 1,600 banana varieties for their potential disease resistance and nutritional variety. The plants hibernate in test tubes under slow-growth conditions — around 61 degrees Fahrenheit — or are cryopreserved at about 320 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, available for resurrection should the need ever arise.

“There are scientists who have been working for decades and decades to get this all set up,” Mr. Sachter-Smith said. “I just come in for the fun part at the end. I’m invited in with special banana eyes.” Sometimes he is invited to a nature reserve or a hospital’s garden. “Sometimes it’s a road trip, and I have my head out the window looking at every banana plant we pass by,” he said. An unusual fruit or leaf prompts a stop. “The fundamental thing: You’re standing in the field. There’s a banana in front of you. Should you collect it or not?”

The banana plant, which falls under the genus Musa, is not a tree but an enormous herb. Researchers believe that the banana ancestor Musa acuminata was first domesticated in Kuk Swamp, an archaeological site in Papua New Guinea, around 7,000 years ago. The plant traveled around Asia and the South Pacific, changing as it went.

On the island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea, Mr. Sachter-Smith identified 170 varieties. On the neighboring island of Bougainville, his team collected 61. The Cook Islands yielded 18, and Samoa 15. He has also hunted bananas in China, Vietnam, Laos, Indonesia, Uganda, Rwanda, Fiji and the Solomon Islands.

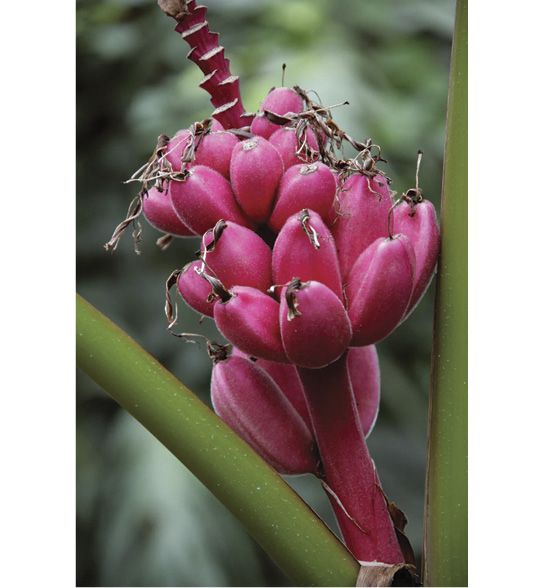

What looks like the banana’s trunk is its pseudostem, a wet layering of leaf sheaths around a soft core, from which the long leaves sprout up and unfurl like sails. Sticking out from between the leaves is the peduncle, which carries the inflorescence, whose female flowers develop into fruits (technically berries) and whose male flower droops down like a purple, engorged heart. To Mr. Sachter-Smith, each part can provide a clue to the plant’s genetic makeup.

“He recognizes different bananas in the field due to the flower, the shape of the leaves,” said Matthieu Chabannes, a molecular biologist at the French Agricultural Research Center for International Development, or CIRAD. During a month of travel in Southeast Asia several years ago, Mr. Sachter-Smith taught the scientist to identify how many sets of chromosomes are in a plant. “If the leaves are very straight up to the sky, they are more likely diploids,” Dr. Chabannes said. A triploid’s leaves bend to 45 degrees, while a tetraploid’s are more horizontal, he said. “Above 95 percent of the time, he’s right.”

During his time at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Mr. Sachter-Smith planted and tended “guerrilla” bananas around campus, according to his classmate and fellow plant-lover Mike Opgenorth, the director of the National Tropical Botanical Garden’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve on Maui. “He had his spots,” Dr. Opgenorth said.

After he graduated, in 2011, Mr. Sachter-Smith embarked on his first documenting mission, to the Solomon Islands. Upon his return, he completed his master’s degree, studying how 80 different banana genotypes reacted to bunchy top virus, a disease that ruins a banana plant’s potential to fruit. But he walked away from a doctoral degree — the traditional path of a banana expert — to keep working face to face with bananas as a farmer. “I’ve just spent a lot, a lot of time staring at banana plants and thinking about how they’re different,” he said.

In 2016, Mr. Sachter-Smith flew to Bougainville in Papua New Guinea for his first paid consulting gig. Julie Sardos, a geneticist at the Bioversity International research group, needed Mr. Sachter-Smith’s “magic eye,” she said.

In one village, the researchers found a banana called Navente, which meant “a part of something” in an extinct local tongue. The Navente, bearing fruit that could grow to the size of a man’s arm, was central to the creation story of the local Barapang tribe, whose young people had lost interest in its preservation. The researchers offered to bring a sample of Navente to Papua New Guinea’s national collection and the international gene bank, for safekeeping. Taking the plant from the area was taboo, but the tribe agreed that doing so would be best for the plant’s future. In another village, Mr. Sachter-Smith noticed a tall plant that looked like a wild ancestor crossed with a common edible variety. He likened it to a fox mixed with a dog, a hybrid that shouldn’t exist. “But in New Guinea, you have stuff like this that breaks the rules,” he said. A genomic analysis later revealed that it was indeed one-half common banana and one-half Fe’i, a vertically fruiting plant so ancient that it is described in Samoan legend: After defeating the lowland banana in battle, the Fe’i raised its head in pride while the loser, humiliated, never raised its head again. (Most bananas fruit on a drooping stem.)

“He saw that right away,” said Dr. Sardos, who has been on three more trips with Mr. Sachter-Smith since 2016. He can recognize a new banana like a new face, she said: “He has this specific skill — gift.”

How many bananas remain at large is a mystery that still captivates Mr. Sachter-Smith. His most recent gig took him to Malaysia and Laos, but he would like to go to northeast India, where wild bananas are rampant. “If you’re going to look for new wild bananas, that’s the place,” he said. “I’m freelance, so it’s like, let me know, I’ll be there.”